What Could Be?

The thread through all of this is that we don’t know what will happen, but we do know what could happen - we don’t know the answer, but we can at least ask useful questions. The key challenge to any assertion about what will happen, I think, is to ask ‘well, what would have to change?’

Capital Thinking • Issue #590 • View online

A lot of really important technologies started out looking like expensive, impractical toys.

The engineering wasn't finished, the building blocks didn’t fit together, the volumes were too low and the manufacturing process was new and imperfect. In parallel, many or even most important things propose some new way of doing things, or even an entirely new thing to do.

So it doesn’t work, it’s expensive, and it’s silly. It’s a toy.

Some of the most important things of the last 100 years or so looked like this - aircraft, cars, telephones, mobile phones and personal computers were all dismissed.

But on the other hand, plenty of things that looked like useless toys never did become anything more.

-Ben Evans

Not even wrong: ways to predict tech

"That is not only not right; it is not even wrong" - Wolfgang Pauli

This means that there is no predictive value in saying ‘that doesn’t work’ or ‘that looks like a toy’ - and that there is also no predictive value in saying ‘people always say that’

As Pauli put it, statements like this are ‘not even wrong’ - they do not give you any insight into what will happen. You have to go one level further.

You have to ask ‘do you have a theory for why this will get better, or why it won’t, and for why people will change their behaviour, or for why they won’t’?

“They laughed at Columbus and they laughed at the Wright brothers. But they also laughed at Bozo the Clown.”

- Carl Sagan

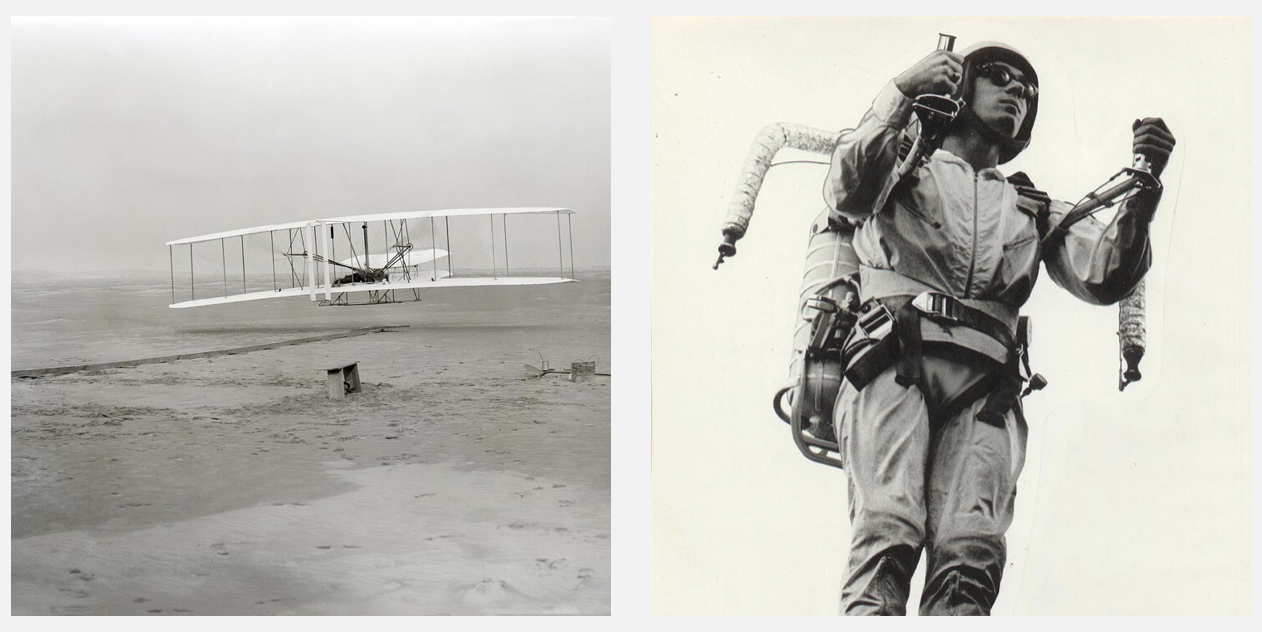

To understand both of these, it’s useful to compare the Wright Flier with the Bell Rocket Belt.

Both of these were expensive impractical toys, but one of them changed the world and the other did not. And there is no hindsight bias or survivor bias here.

The Wright Flier could only go 200 meters, and the Rocket Belt could only fly for 21 seconds. But the Flier was a breakthrough of principle.

There was no reason why it couldn't get much better, very quickly, and Blériot flew across the English Channel just six years later. There was a very clear and obvious path to make it better.

Conversely, the Rocket Belt flew for 21 seconds because it used almost a litre of fuel per second - to fly like this for half a hour you’d need almost two tonnes of fuel, and you can’t carry that on your back. There was no roadmap to make it better without changing the laws of physics.

We don’t just know that now - we knew it in 1962.

These roadmaps can come in steps.

It took quite a few steps to get from the Flier to something that made ocean liners obsolete, and each of those steps were useful.

The PC also came in steps - from hobbyists to spreadsheets to web browsers.

The same thing for mobile - we went from expensive analogue phones for a few people to cheap GSM phones for billions of people to smartphones that changed what mobile meant. But there was always a path.

The Apple 1, Netscape and the iPhone all looked like impractical toys that ‘couldn’t be used for real work’, but there were obvious roadmaps to change that - not necessarily all the way to the future, but certainly to a useful next step.

----------

Finally, sometimes you have a roadmap but discover that it runs out short of the destination.

*Featured post photo by Jonathan Lampel on Unsplash