What Comes Next

There’s a huge amount of innovation and a huge amount of primary technology creation going on at the moment, but there always is - the question here is how universal something could become.

Capital Thinking • Issue #743 • View online

For as long as most people can remember, the tech industry has had a new centre roughly every fifteen years.

A model of computing sets the agenda, and the company or companies that win that model dominate the industry, and everyone is scared of them, and then a new model comes along, forms a new centre, and the old model stops mattering.

Mainframes were followed by PCs, and then the web, and then smartphones.

What comes after smartphones?

Each of these new models started out looking limited and insignificant, but each of them unlocked a new market that was so much bigger that it pulled in all of the investment, innovation and company creation and so grew to overtake the old one.

Meanwhile, the old models didn’t go away, and neither, mostly, did the companies that had been created by them.

Mainframes are still a big business and so is IBM; PCs are still a big business and so is Microsoft. But they don’t set the agenda anymore - no-one is afraid of them.

Today, multitouch smartphones are getting on for 15 years old, and the S curve is flattening out. All the obvious stuff has been built, Apple and Google won, and the new iPhone isn’t very exciting, because it can’t be. So, we ask “what’s the next generation?”

There are several ways to try to answer this.

First, each of the previous S Curves unlocked a dramatically new market, but well over 4bn people have a smartphone today and there are only 5.7bn adults on earth. We can’t unlock a radically bigger market on that axis - we’ve run out of people.

Yes, we will probably deploy billions more sensors around the world, but a street light that phones home if the bulb fails is not a new platform, even if it uses a neural network (AI!) and a radio (5G!). So, in one important way, that growth model seems to be complete.

A second approach would be to ask - ‘what’s in the labs?’

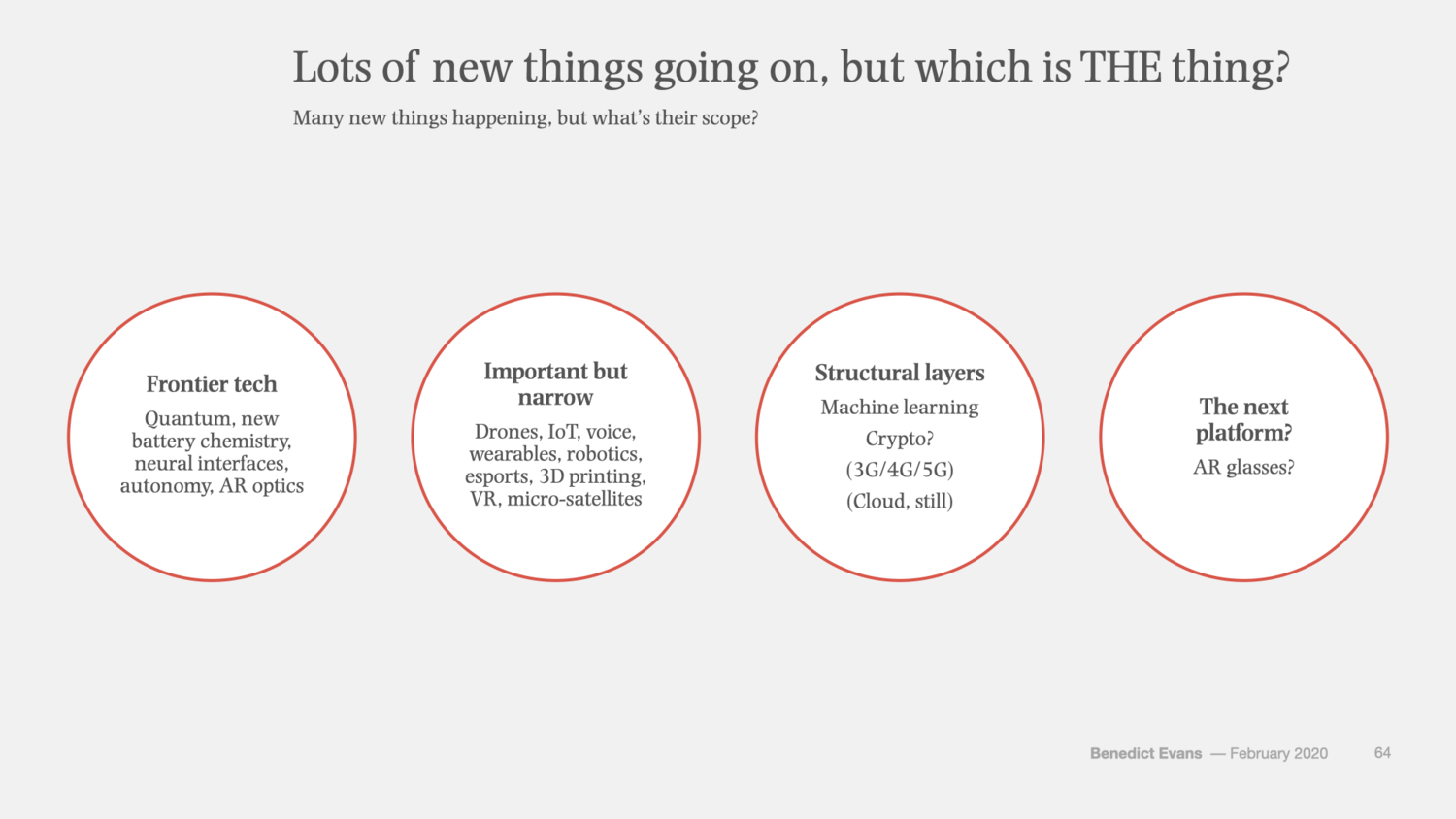

I made this slide for a presentation I gave in Davos at the beginning of the year (which now feels like a decade ago) - I’m sure people will disagree with my allocations, but the point is to try to think about the stages and applicability.

There’s a huge amount of innovation and a huge amount of primary technology creation going on at the moment, but there always is - the question here is how universal something could become.

Hence, most of these could be very important to society, but plant-based meat or micro-satellites are not a model to replace smartphones or search as primary levers of the tech industry.

Theoretically, a neural interface of some kind could do that, but the technology to make that more than a way to turn on a light or open a door seems to be decades away - this is science fiction, not a forecast.