Trust, but verify

Pilots use multiple dials, employing different sources of energy, to report identical data, because they understand that in a dashboard full of information, something is always lying to you.

By Capital Thinking • Issue #1048 • View online

We had been flying for four hours, but both gas gauges still read “full.”

I didn’t need a pilot’s license to know that couldn’t be right, nor to feel the rush of adrenaline in my gums at the thought of the engine sputtering to an eerie quiet death, propeller blades windmilling as we scream “mayday mayday” and “set it down over there” like in the movies, hopefully including the part where the heroes confidently stride away while the wreckage ignites in a fireball, such a banal event in their exhilarating life that they can’t even be bothered to glance back at the carnage.

Who’s lying?

“Umm, this can’t be right” I said to Gerry, the real pilot. “Yeah,” he said, “the needles get stuck to the glass.”

He flicked the glass a few times. They didn’t move. “So… do we have enough gas?” “Yeah, we have another hour left, I stuck the tanks before we left.”

“Sticking” means plumbing a wooden dowl through top of the wing, into the gas tank, judging the gas level by the height of the resulting wetness.

Sometimes the simplest technology is best. Wooden sticks don’t run out of batteries or make you wait forty-seven minutes for a security update.

Trust, but verify.”—Ronald Regan, repeating a Russian rhyming proverb: Доверяй, но проверяйIt’s not even good enough to just have “two of everything.”

If two things both rely on electricity, and the electricity goes out, you lose both.

There were two gas gauges; both failed for the same reason. It needs to be differently-implemented as well, like a stick versus a gauge.

For example, there’s a normal magnetic ball compass floating in liquid that will work even if other power sources fail, but it’s hard to read as it bounces around from the vibration so it’s good to have another one that runs off suction—air pressure differential between the outside and inside of the cabin—which is stable even when you’re turning the plane in turbulence.

Gerry used to say: “Who’s lying?”

Usually your instruments are correct, but sometimes one is lying. Maybe the suction system isn’t working, so you double-checking suction-based dials with the electric-based dials. You stick the tank, in case the gas gauge is lying.

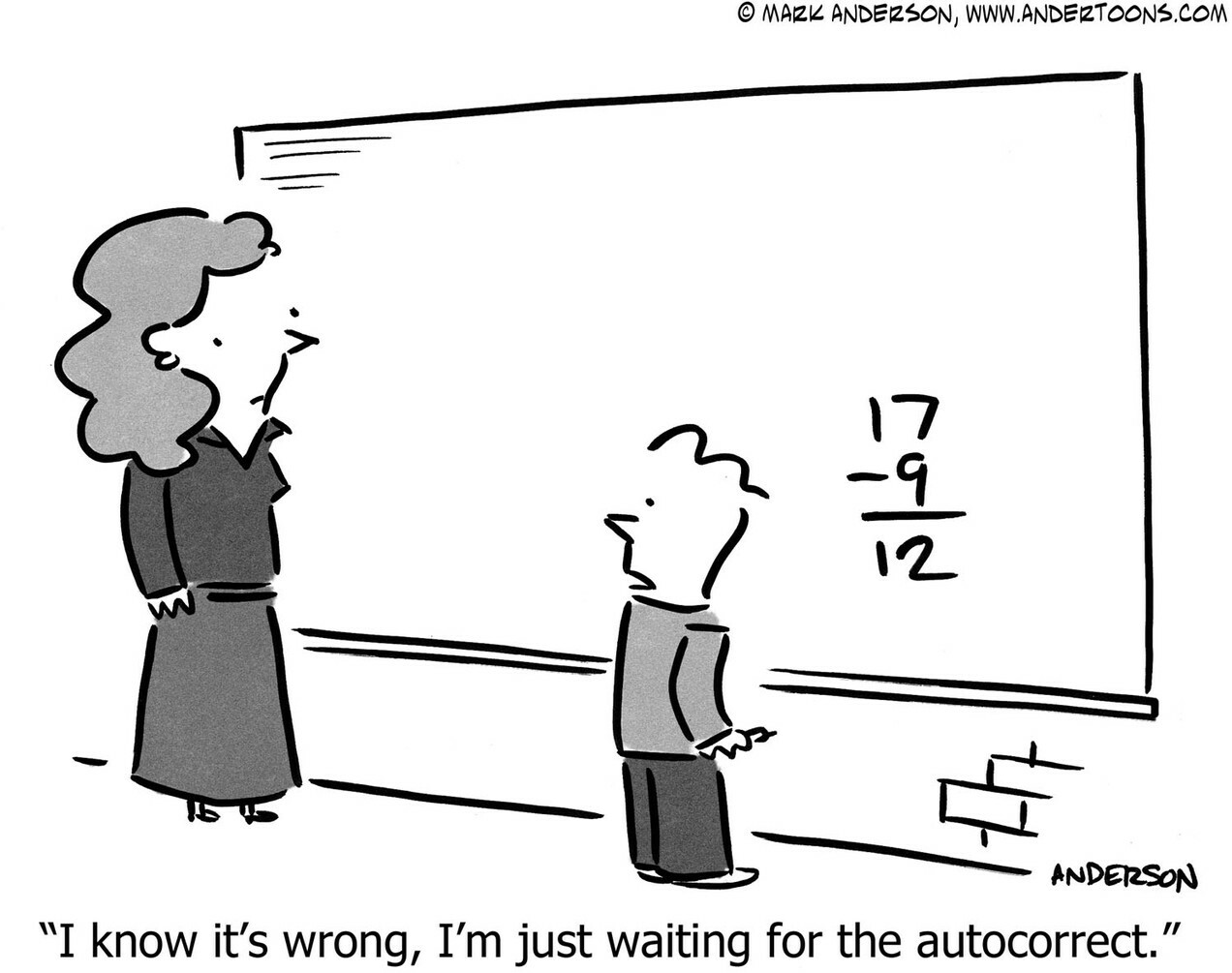

The same lesson applies to our daily life of data and metrics. You think you understand what each number means, and usually you’re correct. But sometimes you’re running out of gas and don’t realize it.

I’ve seen this happen for all sorts of reasons: The spreadsheet had a subtle bug in a formula, the analytics JavasScript code was accidentally left off one page, the survey email didn’t get sent to all the customers in the cohort, the database query did/didn’t filter something important, a nightly update script hasn’t been running for three months.

A good way to check for bad data is to replicate the airplane dashboard method of deriving the same information in two different ways.

Pilots use multiple dials, employing different sources of energy, to report identical data, because they understand that in a dashboard full of information, something is always lying to you.

Photo credits:

(1) Edgar Chaparro on Unsplash

(2)Museums Victoria on Unsplash