THE WORLD'S TALLEST BUILDING

The rapid construction schedule ended up shaping almost every aspect of the building. Primarily, this meant the design of the building needed to be as simple and repetitive as possible.

Capital Thinking • Issue #1157 • View online

Like most “tallest building in the world” projects, the size of the Empire State Building was partly an exercise in building economics, and partly the result of a desire to build the tallest building.

Building Fast and Slow: The Empire State Building and the World Trade Center (Part I)

Brian Potter | Construction Physics:

The Empire State Building was completed in 1931. At a height of 1250 feet [0], it was the world's tallest building, exceeding the recently completed Chrysler building by 202 feet.

It would hold that title for the next 39 years, until 1970 when it was surpassed in height by another New York skyscraper, the under-construction World Trade Center, which would reach a height of 1368 feet on the North Tower.

The World Trade Center would hold that title for just 3 years, after which it would be surpassed by the 1451 foot Sears (now Willis) Tower, already under construction when the World Trade Center was being built. [1]

The Empire State Building and the World Trade Center make for an interesting comparison. In many ways, they’re similar.

They’re both iconic Manhattan skyscrapers (they were built just 3 miles apart) that sit right next to each other in the sequence of “world’s tallest building”.

Both started out as projects aimed at creating (among other things) a large amount of commercial office space, and were later nudged by their owners into becoming the world’s tallest building. Both were completed in the midst of a severe economic downturn (the Great Depression and the 1973 Oil Shock, respectively), and took many years to be fully occupied.

The Empire State Building would be only partially occupied through the 1930s (making money largely from visitors to the observation deck), and the owners were only saved from bankruptcy because the lender (MetLife) didn’t want the building.

It wouldn’t start to turn a profit until after WWII. Similarly, the World Trade Center didn’t reach full occupancy in 1980. In both cases the building owners had to coerce government agencies to use much of the available space.

They also share an architectural genealogy - the architect of the World Trade Center, Minoru Yamasaki, had worked for several years at Shreve, Lamb, and Harmon, the architectural firm that designed the Empire State Building.

But in many ways they’re different. The Empire State Building is often the first example reached for by those nostalgic for an America that builds.

Not only was it built impossibly fast by modern standards (less than a year from setting the first column to being completed), but it came in under budget, with its design becoming a widely praised example of Art Deco architecture.

The World Trade Center, on the other hand, was continuously mired in controversy and difficulty. It was slowed by lawsuits from displaced residents, political opposition from both New York and New Jersey, difficult site conditions, union strikes, and novel building systems and construction methods.

From its conception in 1961 (and arguably even earlier) the project took more than 10 years to complete, going far over its planned schedule and budget. Its architecture would be widely criticized (or at best ignored), as would the urban renewal concept at work behind the project - the World Trade Center has been described as representing the opposite of Jane Jacobs’ worldview, which has since become ascendent in urbanist thinking.

This isn't quite a contradiction (building projects are high variance), but it's an interesting contrast - what made two seemingly similar projects develop so differently?

Why did building the Empire State Building go so smoothly, and the World Trade Center struggle? What can we learn by comparing the two projects?

Let's take a look.

The Empire State Building

The Empire State Building was the brainchild of two men, John Raskob and Al Smith. Raskob was a wealthy businessman who had started his career as Pierre DuPont’s secretary, eventually working his way up to being an executive for DuPont and General Motors.

Smith was a 4-time governor of New York and a friend of Raskob. When Smith ran for president in 1928, Raskob resigned his position at GM to serve as his campaign manager. After losing the election to Hebert Hoover, the two men were looking for a new project.

At the same time, a real estate deal to tear down the Waldorf-Astoria hotel and construct a 50-story commercial office building had fallen through when the developer couldn’t secure secondary financing.

Smith became aware of the deal through his position on the board of MetLife (which had supplied the initial financing), and saw it as a prime opportunity - not only could the property be obtained for cheap, but the Waldorf sat on an enormous lot, 425 feet long by 198 feet wide.

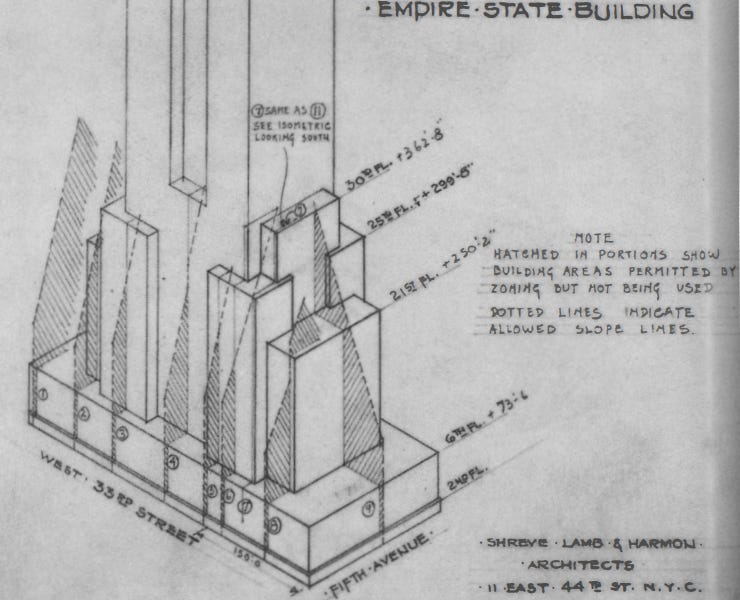

New York’s zoning code at the time restricted building height by way of requiring step backs from the street, but allowed a tower of unlimited height on 25% of the lot. A lot the size of the Waldorf’s (which were rare, and difficult to assemble) would allow the construction of a truly enormous building.

Neither Raskob nor Smith had any experience in real estate development, and it’s arguable whether the site was suitable for a large commercial building - on the one hand, it was near one of the busiest intersections in the world, the intersection of Broadway and 6th Avenue at 34th street, which was crossed by 6 different sets of train tracks. On the other hand, it wasn’t in an office district, or directly on any train lines.

The tallest nearby building was the Internal Combustion Building, a mere 28 stories. Regardless, Raskob and Smith, along with some of Raskob’s wealthy associates (including Pierre DuPont) formed the Empire State Building Corporation, and acquired the property.

On August 29th, 1929, they announced they planned to build an 80-story, 1000-foot-high skyscraper on the site.

By September 9th, the architect was brought on board - Shreve, Lamb and Harmon, the firm that had been engaged to design the previously planned 50 story building.

Two weeks later, the general contractor, Starrett Brothers and Eken, was chosen. By October several design schemes had been floated, with the seventeenth version (Scheme K) chosen.

Building Design

Like most “tallest building in the world” projects, the size of the Empire State Building was partly an exercise in building economics, and partly the result of a desire to build the tallest building.

An expensive piece of real estate is a large fixed cost (it’s estimated that even at a discount, the property cost $16-17 million, or nearly $300 million in 2022 dollars), and the more rentable area you can spread that cost over, the better.

But when building tall, each story is proportionally more costly to build - building taller means a heavier structure, more complicated mechanical systems, more elevators, etc.

Adding more stories to a building increases the return on investment only up to a point, which is typically much less than the height it’s physically possible to build.

*Featured post photo by Osman Rana on Unsplash