The Art of the Con

Some lessons in sales and trust from the man who tried to sell the Eiffel Tower twice.

Capital Thinking • Issue #526 • View online

Trust is a huge component of the sales process because we prefer doing business with likable, trustworthy people.

When our ancestors were in small tribes and villages, the people around us were those we trusted the most, so our brains are hardwired to be more comfortable with people who seem trustworthy.

Unfortunately, this is a double-edged sword as the people who often seem the most trustworthy are also the ones who possess the ability to take advantage of you.

The Man Who Tried to Sell the Eiffel Tower (Twice)

Ben Carlson | A Wealth of Common Sense:

The Eiffel Tower is one of the most recognizable and well-trafficked monuments in the world.

It’s estimated that each year more than 6 million visitors wait in long lines to experience this gorgeous landmark.

It may be hard to believe, but when it was built the tower was subject to ridicule and was only supposed to stand for 20 years before being disassembled.

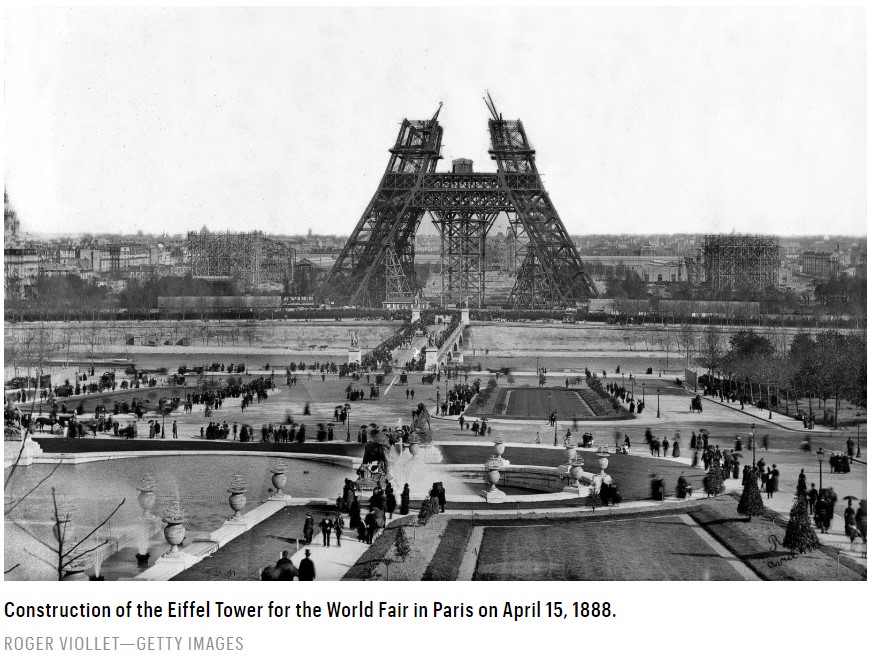

Gustave Eiffel designed his namesake tower for the 1889 World’s Fair in Paris.

No one had ever built a structure so tall before, so the fact that it was erected in just over two years is a technical feat that was unparalleled at the time.

Naysayers told Eiffel the tower would be impossible to build. The wind would make it too dangerous for people to ascend to such heights, and the government wasn’t keen on spending an estimated $1 million on the project.

Eiffel’s contract stipulated that the tower would be allowed to stand for 20 years to be able to earn enough of a profit to make it worthwhile, at which point the erector set-like structure would be taken down piece by piece.

The engineering and construction involved required an incredible amount of precision.

The iron plates used to build the tower would have stretched 43 miles long if they were laid end-to-end and called for over 7 million holes to be drilled into them.

The iron used to construct the tower weighed over 7,000 tons and required more than 60 tons of paint.

Each piece was traced out to be accurate within a tenth of a millimeter. Including the flagpole at the top, the Eiffel Tower reached 1,000 feet in height when it was finished.

Although the tower was more beautiful than most could have imagined, it was initially panned by critics.

Many of France’s leading artists and intellectuals derided the tower, calling it “a truly tragic streetlamp” and an “iron gymnasium apparatus, incomplete, confused, and deformed.”

The Americans and Brits weren’t fans either, mostly because they were jealous.

The New York Times called it “an abomination and eyesore.” Editors at the Times of London referred to it as a “monstrous erection in the middle of the noble public buildings of Paris.”

Americans didn’t appreciate how the Eiffel Tower surpassed the Washington Monument as the tallest man-made structure at that time.

Once it was completed even the most ardent critics eventually came around to the fact that it was a masterpiece, yet the government still wasn’t positive it would keep the structure in place forever.

In the years after the tower was built it began to fall into disrepair. It was costing the city a fortune in maintenance and upkeep.

A man by the name of Victor “The Count” Lustig saw this situation as an opportunity to profit from the uncertainty surrounding the future of this magnificent monument.

Lustig decided he would sell the Eiffel Tower to the highest bidder, not once but twice.