Survival is the Exception

The intoxicating power to nullify people instead of hypotheses is irresistible, and Sagan’s dark predictions will prove true.

Capital Thinking • Issue #1194 • View online

“Extinction is the rule. Survival is the exception.” – Carl Sagan

“There's two kinds of dangers. One is what I just talked about.

That we've arranged a society based on science and technology in which nobody understands anything about science and technology, and this combustible mixture of ignorance and power, sooner or later, is going to blow up in our faces.

I mean, who is running the science and technology in a democracy if the people don't know anything about it?

And the second reason that I'm worried about this is that science is more than a body of knowledge. It's a way of thinking. A way of skeptically interrogating the universe with a fine understanding of human fallibility.

If we are not able to ask skeptical questions, to interrogate those who tell us that something is true, to be skeptical of those in authority, then we're up for grabs for the next charlatan – political or religious – who comes ambling along.”

-Carl Sagan, 1996

Wide Awake

by DOOMBERG

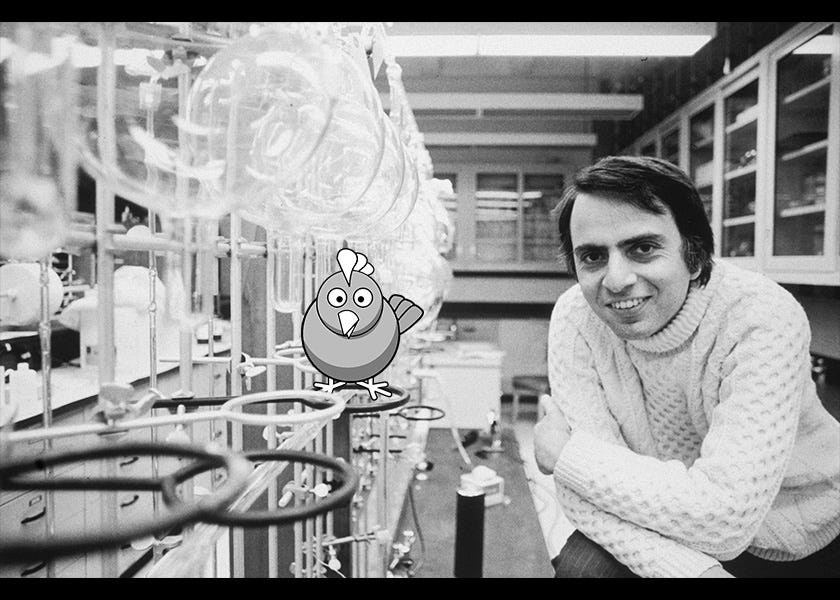

Carl Sagan was a brilliant scientist, gifted orator, skilled teacher, and effective advocate for his strongly held beliefs. It is no exaggeration to say that Sagan is likely responsible for inspiring more people to pursue a career in the sciences than any other person in history.

His 13-part television documentary Cosmos: A Personal Journey – which first premiered on PBS in 1980 and is still stunningly well-worth watching to this day – is widely regarded as one of the best science-themed series ever produced. Sagan knew how to turn a phrase to enchant an audience and routinely did so with a level of passion and charisma that cannot be faked.

In the climactic final episode of Cosmos titled Who Speaks for Earth? Sagan makes an impassioned plea for nuclear de-escalation. The first nine minutes of the piece are particularly spellbinding, and the introduction draws to a close with Sagan walking along a rocky shoreline where he delivers a historic monologue (emphasis added throughout):

“The civilization now in jeopardy is all humanity. As the ancient myth makers knew, we are children equally of the earth and sky. In our tenure on this planet, we have accumulated dangerous, evolutionary baggage – propensities for aggression and ritual, submission to leaders, hostility to outsiders, all of which puts our survival in some doubt.

We have also acquired compassion for others, love for our children, a desire to learn from history and experience, and a great, soaring passionate intelligence – the clear tools for our continued survival and prosperity.

Which aspects of our nature will prevail is uncertain, particularly when our visions and prospects are bound to one small part of the small planet earth. But up and in the cosmos, an inescapable perspective awaits.

National boundaries are not evidenced when we view the earth from space. Fanatic ethnic or religious or national identifications are a little difficult to support when we see our planet as a fragile, blue crescent fading to become an inconspicuous point of light against the bastion and citadel of the stars.

There are not yet obvious signs of extraterrestrial intelligence, and this makes us wonder whether civilizations like ours rush inevitably into self-destruction. I dream about it... and sometimes they are bad dreams.”

Like all of us, Sagan was not infallible nor immune from controversy.

He was famously denied tenure at Harvard, presumably because the more senior members of its faculty were uncomfortable with his high-profile public persona. His pacifist views were labeled “unpatriotic” or “soft on communism,” calls which only grew louder after he was arrested at a demonstration outside of a nuclear test facility in Nevada.

To the members of the conservative right at the time, Sagan was likely considered to be a danger to US national security, especially in light of his uniquely effective communication skills.

Sagan was also proven wrong on several high-profile issues of his time.

His hypothesis that a “nuclear winter” would follow a tactical exchange of such weapons created a temporary bout of media hysteria, despite several prominent scientists questioning the underpinnings of his claims.

The Kuwaiti oil fires that resulted from Saddam Hussein’s scorched earth policy during the first Gulf War represented an interesting test case for key elements of Sagan’s hypothesis.

With the fires still burning, Sagan agreed to debate Fred Singer – then professor of environmental science at the University of Virginia and one of Sagan’s fiercest critics on the subject – on the ABC News show Nightline.

Ultimately, Singer was proven right, a fact that Sagan himself acknowledged in a gracious letter he sent to Singer in 1996, days before dying.

Singer himself passed away in April of 2020, and, as this obituary in the New York Times makes clear, his skepticism about the connection between human activity and climate change makes him worthy of cancellation in today’s hyper-politicized environment, regardless of his scientific qualifications, the strength or weakness of his arguments, or the soundness of the evidence he put forward in support of his many varying hypotheses.

Here’s a key passage:

“Even as evidence of the human causes of climate change and its risks to the planet coalesced into a scientific certainty, Dr. Singer argued that the threat of climate change was overblown, that efforts to blunt its effects would cause grievous economic damage, and that the effects of global warming would be largely beneficial.”

By using the oxymoronic phrase “scientific certainty” in a not-so-subtle attempt to denigrate Singer, the author of this obituary, journalist John Schwartz, reveals that he has precisely zero understanding of the definition of science or how the scientific method works in practice.

We suspect Sagan himself would be aghast at Schwartz’s characterization of his fellow scientist and former debate opponent, for Sagan was an unabashed supporter of rigorous, evidence-based thinking who stood ready to reverse previously held views should the data dictate such a shift was necessary.

How is science meant to work?

The purpose of the scientific method is to explain the observable universe.

Scientists develop hypotheses – mental models for how they think certain aspects of the universe can be understood – and they then submit those hypotheses to the scientific community for rigorous criticism.

The entire point of science is to unrelentingly try to nullify hypotheses through experimentation and data collection. The hypotheses that survive the harshest criticisms may eventually graduate to the level of a theory.

If a theory survives several more decades of intellectual attack, it might then graduate to the level of a law, which you can think of as an axiomatic input into the development of yet more hypotheses.

But even laws are susceptible to a single nullifying observation, as Einstein ultimately proved when he nullified Newton’s laws of physics, which had previously enjoyed centuries of status as bedrock axioms of science.

Einstein ultimately gave birth to quantum mechanics, and while quantum mechanics might currently explain much of the universe as we can observe it, it too stands one reproducible data point away from nullification.

If you are in favor of limiting criticism of scientific hypotheses or constraining debate about the meaning of evidentiary data, science grinds to a halt.

Even if you think the people doing the critiquing are being disingenuous, or they are funded by nefarious characters seeking to exploit ambiguity for monetary gain, or you convince yourself that the mere airing of such critiques is a danger to society, the moment you give in to the temptation to censor counterarguments – to label them as misinformation, for example – you’ve lost.

Either you are willing to outlast your opponents in an extended debate by patiently and calmly rebutting all critiques, or the soundness of your hypothesis must be considered suspect.

Recently, YouTube CEO Susan Wojcicki spoke at the World Economic Forum (WEF) Annual Meeting in Davos and detailed the company’s plans to further limit “misinformation” on its platform.

One does not have to wonder how Professor Singer would be treated by YouTube, one of the world’s most important platforms for information sharing, if he were still alive today.

The powerful company announced in a blog last September that it would demonetize all videos skeptical on climate change, and Wojcicki reiterated this stance in Davos, proudly saying the quiet part out loud:

“And then lastly, we're just really careful about what we monetize.

So, we always want to make sure that there's no incentive. So, for example, with regard to climate change, we don't monetize any kind of climate change material.

So, there's no incentive for you to keep publishing that material that is propagating something that is generally understood as not accurate information.”

*Featured post photo by Nick Fewings on Unsplash