Alpha Decay

Knowledge spreads, technology diffuses, and arbitrages disappear. Markets asymptote towards ever-greater efficiency. This process is extremely well known in capital markets, and even has a name: ‘alpha decay’.

By Capital Thinking • Issue #1047 • View online

Markets rise, and markets fall. This much, at least, is well-known.

But why do market cycles occur?

What causes the pendulum to swing from euphoria to crisis and back?

Minsky Moments in Venture Capital

Hyman Minsky was a 20th-century economist whose ‘financial instability hypothesis’ is probably the best-known explanation for the boom and bust cycles that characterize public financial markets.

But there’s far less examination — in fact, there’s almost none — of how Minsky dynamics apply to private markets.

We’re currently in the midst of an unprecedented boom in private market activity. Tech entrepreneurship, angel investing, and venture capital have never been so widespread. Can Minsky cycles happen in this realm as well?

The Inevitable Briefness of Alpha

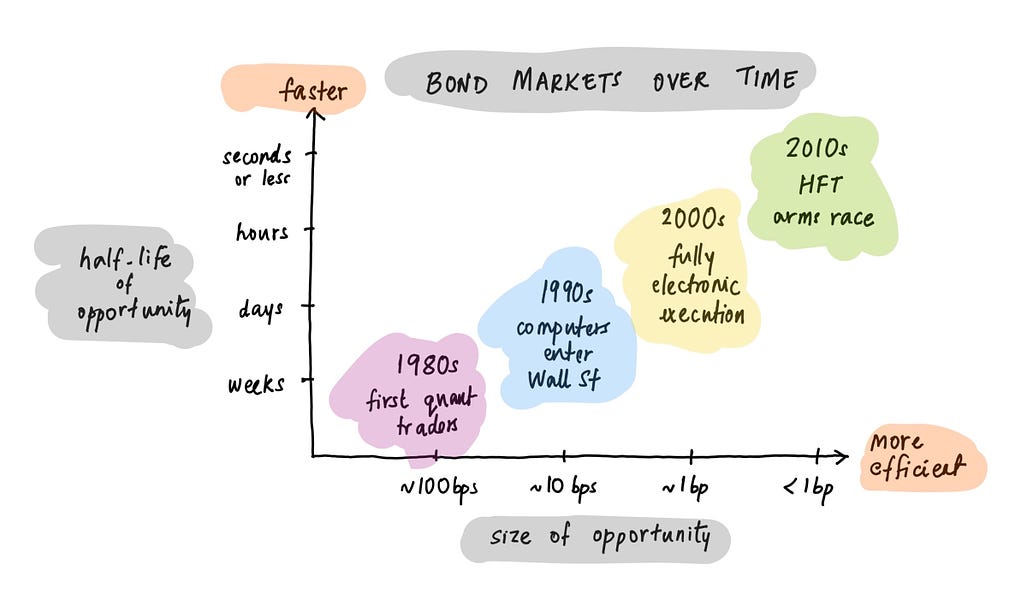

When I started my career as a bond trader at a quant hedge fund, arbitrage opportunities were relatively plentiful. Not many investors had the knowledge or infrastructure to effectively exploit these opportunities, so the early pioneers in the market made good money.

Of course, it didn’t last.

Knowledge spreads, technology diffuses, and arbitrages disappear. Markets asymptote towards ever-greater efficiency.

This process is extremely well known in capital markets, and even has a name: ‘alpha decay’.

Spreads representing 10s or even 100s of basis points of opportunity, common when I started trading, dwindled to mere 1s of basis points less than a decade later.

… Wait, You Did What?

Now, most individuals, when faced with declining opportunities, will reduce their exposure to those opportunities.

If a particular strategy made 10% last year but is only expected to make 1% this year, common sense suggests allocating less capital to it.

But institutions … don’t work like that.

Trading desks have quarterly P&L targets, and traders have annual bonuses they want to make.

There’s a widespread culture of “what have you done for me lately?” — you can’t coast on past success. The implicit call option embedded in most traders’ compensation profiles exacerbates this.

As a result, faced with a 1/10 reduction in expected value for an opportunity, many institutional portfolio managers will actually 10x their exposure to the opportunity, so as to maintain their dollar P&L.

I saw this multiple times in the early 2000s, and it’s completely rational, given their incentives.

Mathematics Made Me Do It

But that’s not the interesting part.

The interesting part is that many risk and compliance models actively encourage investors to do this.

Here’s how it works.

Most risk models (whether implicit or explicit, quantitative or qualitative) measure the riskiness of a particular investment based on how it and similar investments have behaved in the past. Sounds reasonable, right?

Now, suppose that a particular class of investments, that used to be quite risky in the past, has grown less risky in recent years. A model trained on both historical and recent data would say it’s okay to put more capital to work against these investments than in the past; they’re just not that risky any more.

Again, sounds eminently reasonable, right?

“The market is maturing”, is usually how people describe this. Or “The asset class has become more efficient”.

The Illusion Of Safety

Ah, but here’s the catch.

What if it’s precisely the deployment of all this capital that causes the decrease in volatility and hence in perceived risk?

Hyman Minsky fell out of fashion in the 80s and 90s, but his work was rediscovered and widely shared just in time for the GFC.

Today it’s part of the toolkit for most macro (and many micro) investors; you can also see it in regulatory ideas like market circuit-breakers and systemic backstops.