Housing Demand

A way to understand the relative growth in the 21st century is to look at another time in New York history when the population grew rapidly while maintaining relatively affordable housing prices.

Capital Thinking · Issue #945 · View online

Housing Gotham:The 21st Century So Far (Part I)

Jason M. Barr (@JasonBarrRU) and Sean Franklin:

In those years, only a true visionary could have foreseen the city’s rebound. Yet starting in the early 1990s, New York began a dramatic resurgence.

New service-based industries grew in place of the old factory jobs. Crime rates fell, and the decay and despair that had marked the previous years were replaced with reinvestment and optimism.

Economic growth and a sense of security drew people back so that by 2000 the population had recovered to its earlier peak. To this day, the population continues to increase to new highs.

But the laws of supply and demand, being what they are, suggest that, while the city can hold more people, it cannot build fast enough to keep up with demand. The result has been more homelessness, increasing affordability problems, and greater income inequality.

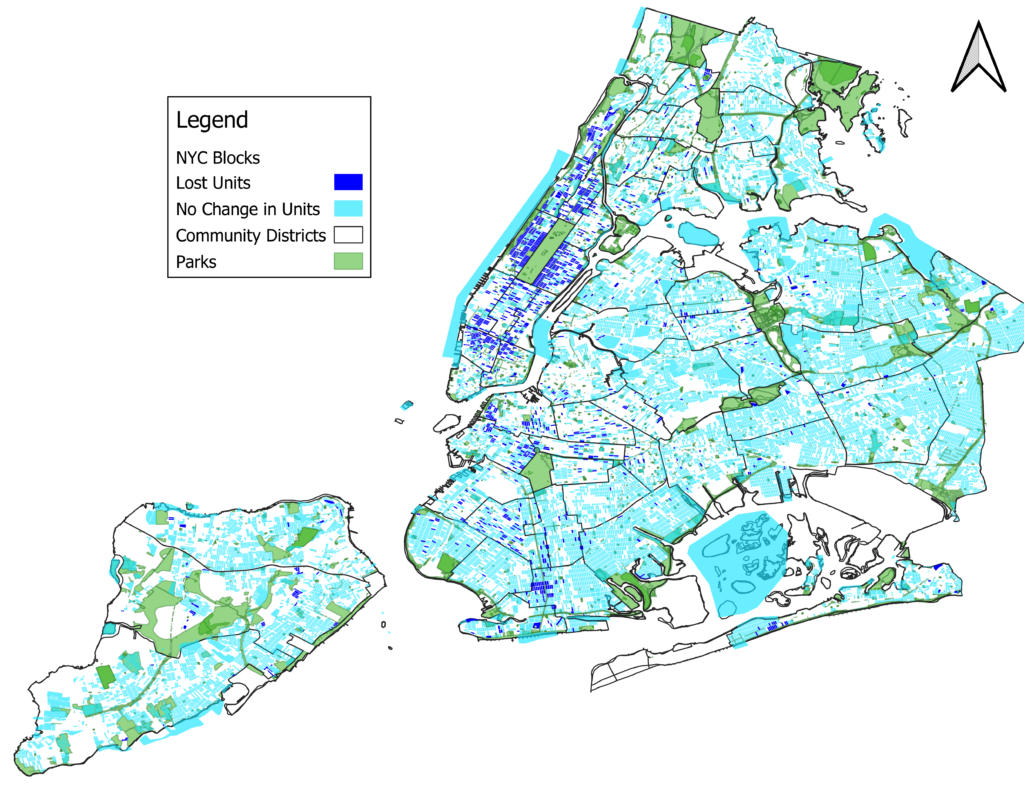

Despite these issues, the questions remain: How has New York’s housing stock changed over the 21st century? Has it grown or shrank? If so, where and why? Which neighborhoods are punching at their weight, and which ones are not doing their part in the great housing game?

To this end, we looked at changes across the Big Apple over the roughly two-decade period from 2002 to 2020 (pre-pandemic) to better understand how and where New York is housing its people. The answers might surprise you.

Counting Houses

One of the benefits of being interested in New York City’s housing market is that city agencies have been on the vanguard of providing large data sets to the public.

One is particularly relevant—the Primary Land Use Tax Output (PLUTO) file—which is online going back to 2002. The PLUTO file includes information about every tax lot in New York City and tells, among other things for each one, the building type, how many housing units it contains, the building height, and so on. The file allows for a very detailed look at the changes in Gotham’s housing supply.

Housing unit additions can appear in three ways: First is through new construction. The second is from the splitting up of extant units within a building. For example, a one-family house can be subdivided into a two-family house. Lastly is through building conversions, where, for example an old office or loft building is refitted for residential use.

The critical point is that we cannot solely rely on new construction measures if we truly want to understand the changes in housing supply. A flexible housing market will depend on all three.

For that matter, there are forces that can shrink supply: Buildings can be demolished, residential units in the same building can be combined, or buildings can be converted to other uses. Thus, the net housing changes across the city depend on both the “adding” and the “subtracting” forces.

Two Decades In

In 2002, the city had about 3.2 million housing units. By 2020, that number was just over 3.6 million units, a growth rate of about 13.5%.In the same period, New York’s total population grew by about 10%. On the surface, this seems promising; the housing stock increased faster than the population.

But the difference of about 3 – 4% is problematic on several fronts.

First, a healthy housing market should have a reasonably high vacancy rate, say between 7-10%. The market should have enough available units so that new people coming in and those switching their housing all have enough choices and are not duking it out over just a handful of options.

Before the pandemic, the city’s overall rental vacancy rate was 3.3%, and 10.5% of rental housing was overcrowded. Furthermore, the vacancy rate for rent-stabilized units was a minuscule 2.06%, while private, non-regulated units were vacant at a 6.07% rate.

Consider that about two out of every three New Yorkers is a renter, and 58% of rental units are regulated or rent-stabilized.

Second, a relatively high number of units—especially in Manhattan—are used as a pied-à-terre or second home, which remain empty for a significant fraction of the year and are not available for residents. One estimate puts that figure at 10,415 units for Manhattan.

While that is only 1% of all Manhattan units, it’s another source “removed” from the local market. This issue is likely made worse by Airbnb, where visitors can soak up “slack” housing.

Household Size

Additionally, the “desired” household size has been shrinking over time. As incomes rise, people are less willing to shack up with roommates, and they want more space. Also, the composition of households is changing.

The proportion of traditional nuclear families with two spouses with children has dramatically fallen. In contrast, households of couples with no children and single-person households have grown in their place. All these various demand-side changes put pressure on New York’s housing stock.

Given the overall difficulty in building, new construction appears mainly at the higher end of the market. So, the average net difference between the population and the housing stock growth might not reflect housing access across all groups.

As a hypothetical example, it may be that the net growth in housing units relative to the population for the upper-income households is 10%. At the same time, for the lower-income folks, it is 1%, leaving an average difference of 4%.

And while recent research shows that even high-end high-rise apartment building construction helps reduce prices, its impact on lower-income residents is less direct.

A way to understand the relative growth in the 21st century is to look at another time in New York history when the population grew rapidly while maintaining relatively affordable housing prices.

Census data from 1910 and 1930 reveal that New York City’s population grew by 45% in the two-decade period, while the number of households (our measure of housing units) grew by 78%.

Prorating that to the 10% population growth seen in the 21st century would suggest housing stock growth would need to have been at least 17% to keep prices in check (assuming, as well, that housing is broadly created for those across the income spectrum).

In short, when we consider all the forces as work, a net gain of housing units of about 3-4% higher than the population growth shows that housing supply is not matching demand across the entire income spectrum.

Photo credit: Carl Solder on Unsplash