Debt and Second Order Consequences

Investors and operators are often deeply misaligned: investors think in bets, while operators think in consequences. The relationship is tense, but can be explosively productive. The VC model is an institutional expression of this tension.

Capital Thinking · Issue #935 · View online

Ten years from now, what seismic change will we reflect back on and think, “well that was pretty obvious, in retrospect”?

Debt is Coming

Debt is going to finally come to the tech industry.

We can hate it, we can criticize it, we can raise the alarm about how dangerous debt is to the VC model we’ve honed to perfection over decades. Or we can see this moment for what it is: a turning point into a new deployment period for software and the internet.

Debt is coming, whether we like it or not. And I’m actually pretty excited for it.

The Deployment Period

When people in tech want to sound smart, one name you can drop is Carlota Perez.

Her book Technological Revolutions and Financial Capital is a rare accomplishment: it’s a top-down “grand theory” book about the innovation economy, written by an academic rather than an on-the-ground practitioner, that actually gets things right.

Read it alongside Bill Janeway’s Doing Capitalism in the Innovation Economy, the number one book that’s most influenced my own thinking.

Technological Revolutions & Financial Capital explores the relationship between Financial Capital (the equity and debt that’s owned by investors) and Production Capital (the factories, equipment, processes, and other real-world concerns which financial capital owns).

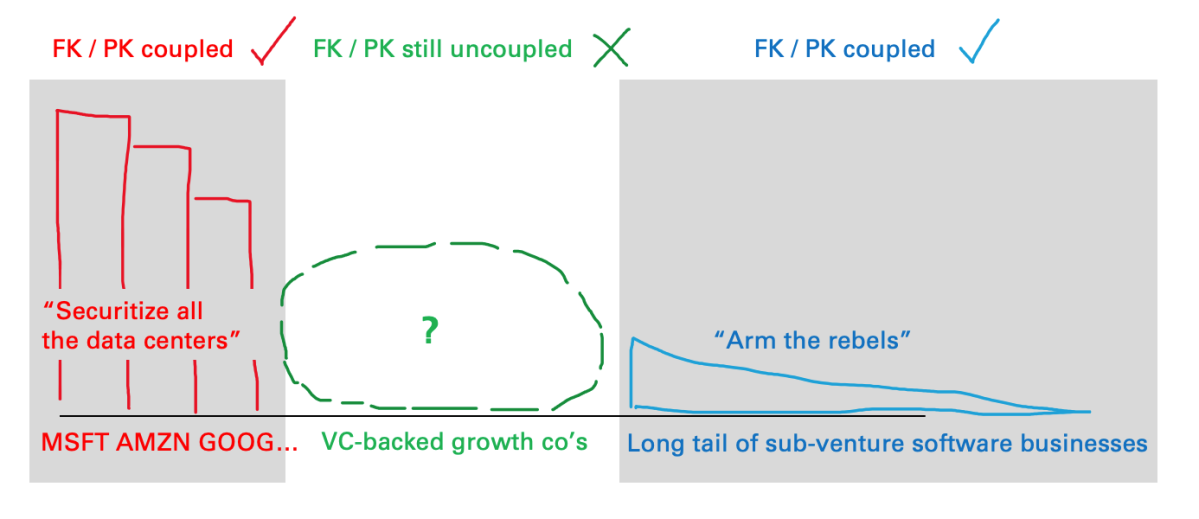

Perez’s core message in the book is that Financial Capital (FK) and Production Capital (PK) have changing but predictable relationships with each other in distinct phases of technological development and deployment.

There’s a recurring dynamic of how FK and PK perceive each other and work with one another. Jerry Neumann’s explanation is good: “My long-ago operations research textbook had a cartoon showing one MBA talking to another: ‘Things? I didn’t come here to learn how to make things, I came here to learn how to make money.’

This is the view of financial capital. The view of production capital is exemplified by Peter Drucker: ‘Securities analysts believe that companies make money. Companies make shoes.’”

In the first phase of a technological revolution, which she calls the “Installation Period”, the relationship between FK and PK is fundamentally a speculative one.

The new technology is exciting, and the market opportunities are large but unknown. Speculative investment, with ambitious but inexact expectations of financial return, is important fuel for founders who build the unknown future.

However, investors and operators are often deeply misaligned: investors think in bets, while operators think in consequences. The relationship is tense, but can be explosively productive. The VC model is an institutional expression of this tension.

In the Deployment Period which follows, FK and PK recouple. We reach a turning point away from speculative financing and towards more aligned investment, where capital gets put to work less exuberantly and more deliberately.

The investor, at this point, has a good understanding of the assets that they’re buying and the cash flows that they will generate. The operator has reasonable expectations around cost of capital, and a tried-and-true game plan for how to put that capital to work making shoes.

This does not look like VC. It looks like regular finance.

Photo credit: Avery Evans on Unsplash